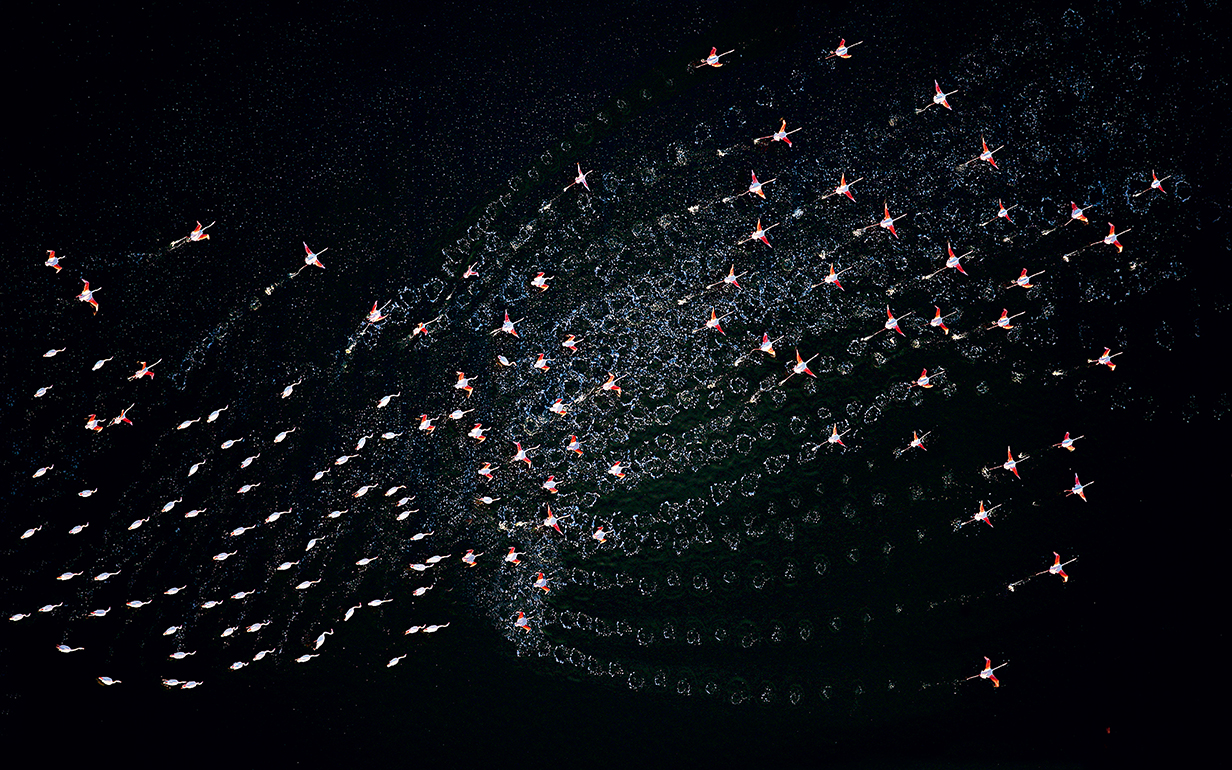

Lake Elmenteita, Kenya. (LUO HONG)

Every time the sun comes up, myriads of animals, plants, and microbes on this planet welcome it alongside us. Regardless of size and shape, every life is valuable. Terrestrial, marine, and other aquatic ecosystems, as well as the ecological complexes they populate, constitute biodiversity, which is the material basis for human subsistence. They provide people with not just food, medicine, and energy, but also cultural and spiritual support.

However, the Earth is ringing alarm bells: Massive loss of forests and wetlands has pushed millions of species to the brink of extinction as persistent challenges thwart global biodiversity conservation. This degradation seriously threatens the survival of future generations, increases the risk of disease outbreak, and impedes achievement of sustainable development goals.

The United Nations General Assembly has scheduled a Summit on Biodiversity for September 30, 2020, during its 75th Session. Although countries around the world are still focused on battling the unrelenting COVID-19 pandemic while grasping for post-pandemic recovery, biodiversity conservation remains a pressing issue. From nature-based solutions to climate, food, water security, and sustainable livelihood, biodiversity issues are essential if we are to ever approach sustainable development.

The COVID-19 outbreak inspired widespread reflection on the relationship between man and nature and prompted new work to find methods to protect biodiversity, reduce the risk of future pandemics, and build an Earth community striving for a better future.

SAVING GLOBAL SPECIES

We are facing a major opportunity to bring nature back from the brink

By Yuan Yanan

Grey herons perch in Haizhu National Wetland Park in Guangzhou, south China’s Guangdong Province, on April 27, 2020. (XIE HUIQIANG)

2020 was supposed to be a big year for nature, with several global climate conferences such as the UN Ocean Conference, IUCN World Conservation Congress 2020, UN Convention on Biological Diversity COP 15, and the meeting of Water and Climate Change set to chart a course for slowing climate breakdown and protecting biodiversity over the next decade. Even though most of these conferences have been postponed due to the outbreak of COVID-19, the biodiversity crisis never observed a shutdown.

“We must embrace, acknowledge, integrate, and act for nature in everything we do,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Program. “We are losing species at a rate 1,000 times greater than at any other time in recorded human history and 1 million species face extinction. We are facing a major opportunity to bring nature back from the brink.”

Biodiversity Crisis

Biodiversity describes the whole range of living things and systems on this planet. It is usually explored at three levels: genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity. These three levels work together to create the complexity of life on Earth.

“Without biodiversity, there is no future for humanity,” said Professor David Macdonald at Oxford University. “Biodiversity sustains human livelihood. The air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, and the energy we use all ultimately rely on biodiversity.”

One study estimates that each year, the goods and services created by the planet’s ecosystems contribute trillions of dollars to the global economy, more than double the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). From an aesthetic point of view, every one of the millions of species is unique—a natural work of art that cannot be recreated once lost.

Biodiversity is fundamental to both planet and people but now it is in crisis. According to the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2019, around 1 million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever before in human history.

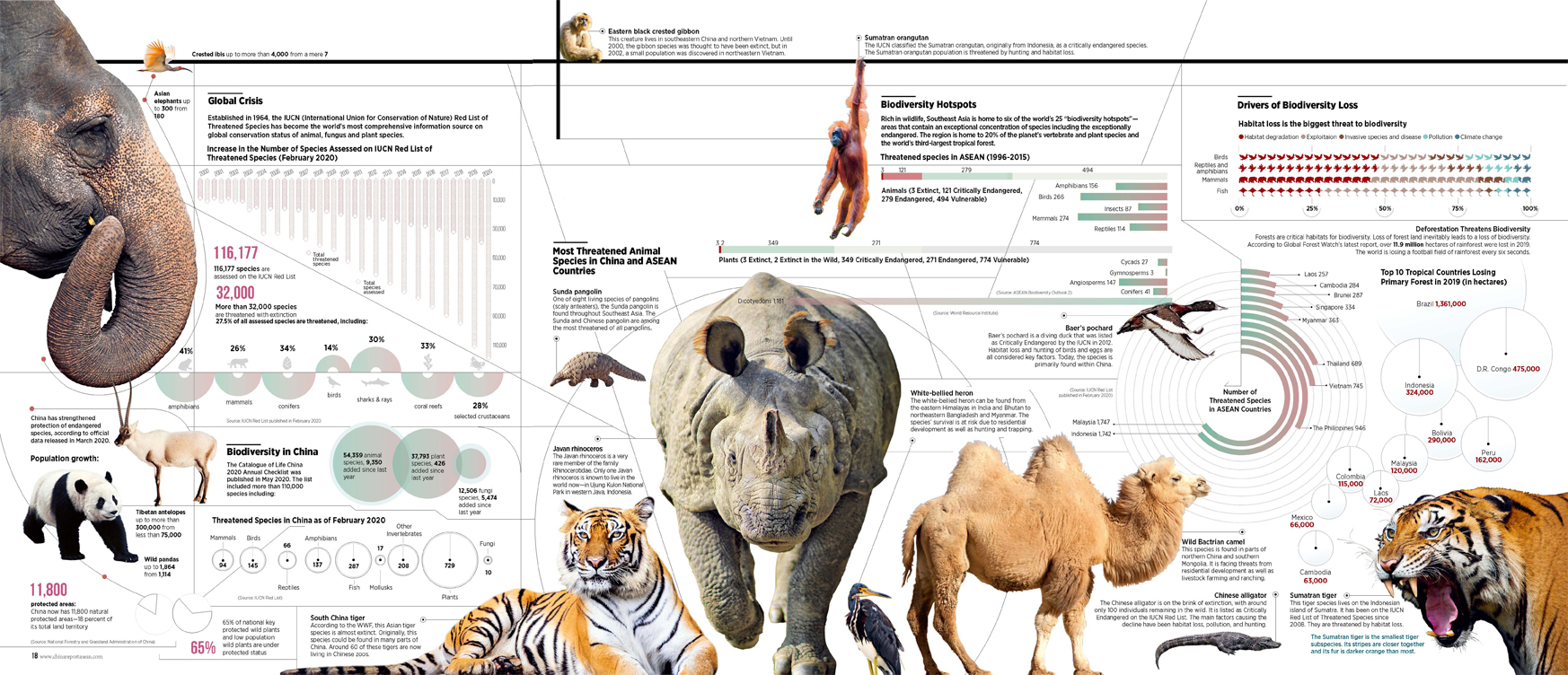

The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20 percent, mostly since 1900. More than 40 percent of amphibian species, almost 33 percent of reef-forming corals, and more than a third of all marine mammals are threatened. The situation is less obvious for insect species, but available evidence supports a tentative estimate that 10 percent are threatened. At least 680 vertebrate species had been driven to extinction since the 16th Century, and more than 9 percent of all domesticated breeds of mammals used for food and agriculture had become extinct by 2016, with at least 1,000 more breeds still threatened. In Asia, many species like the Sumatran orangutan, South China tiger, and Sunda pangolin may soon disappear forever.

“Scientists have identified five mass extinctions in Earth’s history, but the crucial difference is that this time the threat is humans,” said Sandra Diaz, co-chair of the report of IPBES. It defines five main categories of direct drivers to the loss. In descending order, they are changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species.

The report noted that since 1980, greenhouse gas emissions have doubled, raising the average global temperatures by at least 0.7 degrees Celsius, and that climate change is already impacting nature from ecosystems to genetics—impact expected only to grow over coming decades, in some cases surpassing the impact of land and sea use change and other drivers.

Despite some progress on conserving nature through policy, global goals on conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories. Good progress has been made on only four components of the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets (the Aichi Biodiversity Targets for the 2011-2020 period was adopted at the 10th meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity held in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, Japan, in 2010), so it looks increasingly likely that most will be missed by the 2020 deadline. Current negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystems undermine progress towards 80 percent of assessed targets of Sustainable Development Goals related to poverty, hunger, health, water, cities, climate, oceans, and land. Loss of biodiversity becomes more than an environmental issue and affects development, economics, security, social systems, and morale.

“Governments need to integrate biodiversity considerations across all sectors—not just better environmental policies but better policies on agriculture, infrastructure, and trade,” said Sandra Diaz. “It’s all about putting nature and the public good first rather than the narrow economic interests of a minority. It’s as simple—and as difficult—as that.”

Halting Biodiversity Loss

To conserve global biodiversity, the Global Seed Vault has been one successful practice. Deep inside an icy mountain on a remote island in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole lies the Global Seed Vault. The purpose of the facility is to store seed samples from all the world’s crop collections. Millions of seeds from more than 930,000 varieties of food crops are stored in the vault. It is a safety deposit box holding the world’s largest collection of agricultural biodiversity.

The facility, which was fully funded by the Norwegian government in 2008, offers any government access to seeds in case of natural or man-made disaster. The concept was successfully tested in 2015 with a seed withdrawal to help Syria re-establish crops wiped out by the country’s civil war.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, more than 1,700 gene banks are housing food crops around the world. The U.S. has more than two dozen repository centers affiliated with the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System which works to preserve genetic diversity of plants through state, federal, and private organizations.

As one of 17 mega-biodiversity countries which account for at least two thirds of all non-fish vertebrate species and three quarters of all higher plant species in the world, China harbors nearly 10 percent of all plant species and 14 percent of animals on Earth according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The Chinese government considers conservation of biodiversity tremendously important.

China has established more than 11,800 protected areas covering 18 percent of its land area and 4.6 percent of its sea area as part of a drive to build the world’s most expansive mechanism for management of protected areas by 2025, according to an October 2019 announcement from China’s National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

China’s nature reserves, including 35 million hectares of natural forests and 20 million hectares of wetlands, now safeguard 85 percent of the country’s total wildlife and 65 percent of its vascular plants.

From 2016 to 2020, a total of 349 million yuan (US$51 million) was invested to launch major biodiversity conservation projects and organize surveys and assessments of species and genetic resources in important regions. This spending is ensuring China gains adequate understanding of the background of the species, their distribution, threat factors, and protection status.

China has consistently remained active in international cooperation. China has made significant progress on reaching the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, three of which have been achieved ahead of schedule. The COP 15 on Biological Diversity is set to be held in Kunming, southwest China’s Yunnan Province. Many global entities and stakeholders will visit China to promote global biodiversity conservation and formulate a blueprint for the next 10 years.

“The state of biodiversity is not where we would like to have it,” said Inger Andersen. “We can do more as a global community. We are looking forward to the next Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Kunming and hope the world will come together to agree on stronger commitments to protect species.” Andersen has been encouraged by China’s program to restore degraded ecosystems and expressed confidence that Beijing’s ecological civilization model could become a template to guide the global biodiversity conservation agenda.

Both China and ASEAN are rich in biodiversity, and the two have made biodiversity conservation a priority area of cooperation since 2009. To deepen pragmatic cooperation, China and ASEAN countries have organized seminars on topics of ecosystem improvement, conservation of mangroves and peatland, and conducted joint research and capacity building activities. The latest issue of China-ASEAN Strategy on Environmental Protection Cooperation and Action Plan (2021-2025) will strengthen cooperation on biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management, according to the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China.

In 2006, support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) helped several Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) members including Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, China, Thailand, and Vietnam launch joint efforts to reduce ecosystem fragmentation in major trans-boundary biodiversity landscapes in the subregion. The Biodiversity Conservation Corridors Initiative is a flagship component of the program. It is an innovative approach combining poverty reduction with biodiversity conservation.

The evaluation report published by ADB in 2019 found that the program in GMS generated transformative effects by engaging different sectors and developing regional collaborative mechanisms to prioritize environmental concerns. Thanks to the program, improving the capacity of environmental managers has emerged as a higher priority in the region. Still, plenty of work remains to be done to create an environmentally friendly and climate-resilient region for all GMS members.

L0013.T001.JPG

China has established more than 11,800 protected areas covering 18 percent of its land area and 4.6 percent of its sea area as part of a drive to build the world’s most expansive mechanism for management of protected areas by 2025.

L0013.T002.JPG

China’s nature reserves, including 35 million hectares of natural forests and 20 million hectares of wetlands, now safeguard 85 percent of the country’s total wildlife and 65 percent of its vascular plants.

Key Statistics

SUSTAINING TOMORROW

Disruption of the ecological balance could upend everything

“Some evil spell had settled on the community: mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death.”

So biologist Rachel Carson described a fictional American town in her acclaimed 1962 book Silent Spring, which opened with a “fable for tomorrow.” The maladies were caused by indiscriminate application of DDT and other chemical pesticides which were already exerting massive damage on wildlife, livestock, pets, and even humans. It seems unthinkable we would blanket the Earth with such poisons, but we have.

Nature-based solutions to climate, food and water security, and sustainable livelihood all depend on biodiversity—the foundation for a sustainable future. However, socially among humans, full development of production has wide consensus as a must to feed the surging population and maintain economic benefits. Indiscriminate usage of DDT and other pesticides (or biocides) is not the only foreshadow of death. Cold reality is that due to rapid development of industrialization, biodiversity is vanishing at an astonishing rate unseen in human history, all on our watch.

Conquest or Coexistence

The soil on this planet nurtures all kinds of organisms along the ecological food chain. In Carson’s view, all living things on Earth are closely related, all species are interdependent, and all creatures are dependent on Mother Nature. All animals and plants on Earth, upon which man depends, compose this magical and beautiful biosphere. Any disruption of the balance of the sphere could cause disaster to the entire ecosystem.

“Man conquering nature” used to be an expression of a heroic spirit to in some way tame the wilds. While promoting the development of science and technology alongside the advancement of human civilization, humans have often transformed nature according to subjective wishes to get more from it. Reckless interference, abuse, and destruction of nature has left us in an almost insurmountable ecological crisis.

The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) shows that environmental protection rises as a priority alongside economic prosperity. It is conventional wisdom that the environment pays the inevitable price for development. Forest fires across Indonesia have been a problem for years, especially in 1991, 1994, and 1997. Some reports blamed on El Niño for fires, but others estimated that 80 percent of Indonesia’s forest fires in 1997 were caused by big-operation farmers seeking to exploit wilderness.

The EKC is not absolute, however. Lu Zhi, a professor of conservation biology at Peking University and executive director of the university’s Center for Nature and Society, noted that in China’s areas inhabited by ethnic minorities, many people endure difficult lives yet still maintain strong awareness for ecological protection and actively participate in it. In February 2019, an avalanche dropped in Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Qinghai Province. Many local herders spontaneously carried foliage into the mountains to save wildlife. Such behavior is not about monetary incentives or legal obligations, but a response to values. Such efforts are quite inspirational for environmental protection.

Environmental degradation is inseparable from human well-being. Kathy Willis, professor of global biodiversity at Oxford University, has a unique view of the “value” of man and nature. She thinks that people don’t like to put a label of “value” on biodiversity but are forced to. Without trees in the streets, incidence of asthma would increase dramatically. If the positive impact of nature is lost, people would need to rely on more costly but less efficient technological solutions to replace the benefits. Such technology seems like a tall order.

In September 2020, the Summit on Biodiversity will convene on the margins of the 75th session of the UN General Assembly. Xie Yan, associate research fellow at the Institute of Zoology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, thinks that most countries globally are unaware of the significance of biodiversity on the long-term survival of their own people. Heads of state and government in attendance of the summit need to be fully aware that biodiversity conservation is, first and foremost, the duty of a state. Each nation must protect the ecological security of its own people.

Biodiversity & Public Health

In 2020, we experienced some deaths quite different from Carson’s “silent spring.” The outbreak of COVID-19 pressed the “pause” button on cities. Streets that were perpetually bustling with traffic and pedestrians went silent in the blink of an eye. Noisy factories went silent. Everybody was hidden behind a mask and stayed away from others. The coronavirus still spreads across the world, resulting in millions of infections and hundreds of thousands of deaths, not to mention an unprecedented impact on global economics, trade, diplomacy, and social psychology.

Although the source and route of transmission of the virus have not been scientifically confirmed, most studies so far trace the virus to nature. Scientists generally agree that it jumped from natural hosts of wild animals such as bats and pangolin to humans via intermediate hosts.

In recent years, new infectious diseases have constantly emerged around the world such as Hendra virus (HeV), Nipah virus (NV), H7N9 avian influenza, Ebola, SARS, MERS, and many more—all associated with animals. Frequent contact between humans, wildlife, and livestock always risks exposure to infectious diseases that could threaten the health of all. The growth of international trade, including trade of wildlife both legal and illegal, with increasingly convenient transnational transportation of people, has made it easier for infectious diseases to spread regionally and even globally.

Lu Zhi believes that these viruses have existed in nature and evolved in tandem with their hosts for a long time, striking a delicate balance. However, illegal trade and consumption of wildlife, or encroachment into wildlife habitats, can lead to a significantly greater exposure to these viruses among humans and endanger public health security. The trend of globalization, convenience of transportation, and faster movement of people have all increased the risk of infectious disease outbreaks.

The connection between biodiversity and public health security has never been as painfully close as today. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China is making major contributions as a big country rich in biodiversity resources. Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, applauded China’s development philosophy of “ecological progress.” She praised China’s strong determination to prioritize biodiversity through rigorous protective measures such as setting red lines for ecological conservation.

To preserve biodiversity, China enacted the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife back in 1989. A quarter of a century later, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress amended the law to fully ban illegal hunting, trading, transportation, and consumption of wild animals.

Human activity makes a huge impact on the ecosystem. Dr. Li Binbin, assistant professor of environmental sciences at the Environmental Research Center at Duke Kunshan University in east China’s Jiangsu Province, attributed great changes in the ecosystem to human activities such as new land usage, intensive agricultural production, and introduction of antimicrobial agents, which all exacerbate the risk and potential impact of infectious disease outbreaks. Change in land usage is the most important factor contributing to the increase in infectious diseases caused by wildlife. A study in the Amazon Basin found that incidence of malaria increased by 50 percent when forest cover decreased by 4 percent due to human activities such as logging because the hydrothermal conditions in the deforested areas became more conducive to breeding of intermediary host—mosquitoes. In the biosphere, human interference does not often directly change species diversity but increases the probability of transmission of pathogens by affecting species composition and community vulnerabilities.

“This is not simply an ecological environment problem,” commented Wang Huo, deputy secretary-general of the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation. “The dramatic loss of biodiversity is an unprecedented and enormous challenge for humanity. The most important step is to fully mobilize all the people from all walks of life to participate in the protection of biodiversity.”

At the end of her book, Carson wrote: “The people had done it themselves.” She claimed that all kinds of people had some role—rich and poor, men and women, even newborn infants. Today, 60 years later, Carson’s once controversial views are gaining support. Awareness of biodiversity conservation is rising, and people are contributing to it with concrete action. The little improvements are like bird songs in a silent spring—as sign of hope and expectations.

“We are the last generation with a chance to save biodiversity,” added Wang. “It’s not too late to make some changes.”

The offspring of giant panda “Cao Cao” is transferred by keepers in panda costumes to a new location in a tailor-made basket for the second phase of field training in Wolong Nature Reserve, Sichuan Province, on February 20, 2011. (HENG YI)

Assistant police officer Xie Ancheng shares a delightful moment with a baby Tibetan antelope in Hoh Xil, a haven for wildlife and ecological protection in Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province, on August 15, 2017.(ZHANG HONGXIANG)

Hu Shibin, head of a patrol team monitoring the Yangtze River in Anqing, Anhui Province, displays a picture of a dead Yangtze cowfish (Finless porpoise) found on August 9, 2017. Since the end of June 2017, Hu’s team had patrolled the river several times a week. (LIU JUNXI)

Blue sheep in the Qomolangma National Nature Reserve in Tibet Autonomous Region, on April 29, 2020. (PBUZAZI)

L0017.T001.JPG

A study in the Amazon Basin found that incidence of malaria increased by 50 percent when forest cover decreased by 4 percent due to human activities such as logging because the hydrothermal conditions in the deforested areas became more conducive to breeding of intermediary host—mosquitoes.

BIODIVERSITY CRISIS

By Yuan Yanan

According to the United Nations (UN), nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history, and the rate of species extinction is accelerating. About 1 million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction. Experts say that with current trends, by 2100, an estimated 50 percent of all the world’s specieswill go extinct.

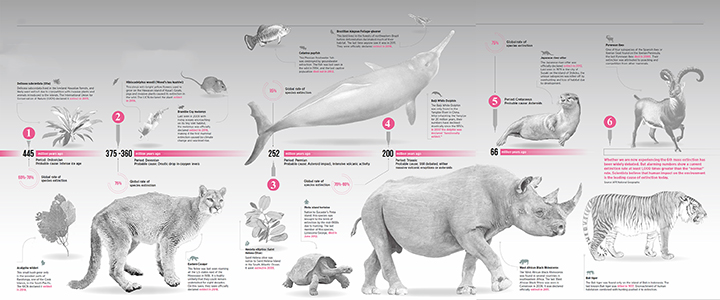

ETERNAL EXTINCTION

By Yuan Yanan

Nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history, and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating. Human activity is the greatest driver of this phenomenon. There is no return from extinction, and loss of a species is an eternal disappearance of one tile in the mosaic of life. It’s a loss for all life on Earth.

A species is declared extinct with certainty only after decades without a sighting. Here are some species we’ll never see again.

SMALLER CITY DWELLERS

Can we find a way to coexist harmoniously with wildlife in cities?

By Yuan Yanan

On the evening of July 7, Shanghai resident Chen Yuanyuan was out on an after-dinner walk on a cobble-stone path in her residential area, wearing pants and slippers, when a racoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) the size of a cat darted through the high grass. The animal scratched the back of her heel before leaning its tiny head on her ankle. “I felt it clinging to my ankle when it suddenly jumped back into the high grass on the other side of the path,” said Chen.

The incident resulted in a large gash on Chen’s foot. In the hospital emergency room, she was vaccinated for rabies. Since then, the formerly fearless woman has refrained from going out at night. When she takes a walk in her neighborhood, she dresses more carefully and wears proper shoes.

News of Chen’s encounter with a racoon dog jolted the nerves of the whole neighborhood. The neighborhood committee received more complaints about the racoon dogs as well as requests to have them moved or caged.

The incident drew the attention of Wang Fang, a researcher at the School of Life Sciences of Fudan University, who specializes in wildlife population, community ecology, and conservation biology. In recent years, he led a team of volunteers to survey the racoon dog population in Shanghai.

The racoon dog is a canid indigenous to Shanghai which has been fortunate enough to enjoy a population increase in recent years, with its habitat expanding from the city’s west end to the east. Wang Fang sees this as a sign of the city’s ecological restoration. The racoon dog is born timid and doesn’t dare get close to humans, especially before a year of age. Therefore, under normal circumstances, they are unlikely to attack people. After on-site surveys, Wang determined that the woman had encroached on its territory, which indicates an imbalance in the relationship.

“Feeding wild animals is against the laws of nature,” said Wang. “When people feed wild pups, they stop being afraid and keeping a distance.” His survey team witnessed a fierce melee in a residential area over cat food involving dozens of adult racoon dogs as their young ones looked on eagerly.

“New-born racoon dogs should look for new habitats and learn new skills. But human feeding has changed their survival habits and dramatically increased their population. When they fail to get enough from man, they will vent their anger against us,” Wang added.

Such incidents have awoken many to the breadth of the wildlife sharing urban spaces with people. We should figure out how to coexist harmoniously with wildlife in cities.

Adaptation

The rapid process of urbanization has brought about dramatic changes in wildlife habitats. In this process, some wild animals were forced to migrate to habitats more suitable for survival, while others that could not adapt to a new environment vanished forever. In contrast, some viable species have begun to shift habitats to exploit the plentiful resources cities have to offer.

Wang Fang believes that some wild animals have adapted to urban life far faster than we can imagine. For example, the North American raccoon (Procyon lotor) has learned to identify traffic and different types of urban buildings over the last 20 to 30 years. Yellow weasels are generally known as nocturnal animals, but without human interference, they hunt during the day fairly frequently. In urban areas, their day-time activity drops significantly compared to the night. Under natural conditions, if a person approaches nests or habitats of badgers or racoon dogs, they growl ferociously and attack quickly. In urban environments, however, they tend to be more tolerant.

From a biological evolution perspective, urbanization is having a profound impact on species. In 2008, a French scientist hypothesized that urbanization has already affected the evolution of species. He noticed that Tibetan hawksbeard roots (a herbal plant) grown in the city produce larger seeds than the same species grown in the countryside. He thought that the heavier seeds would be less likely to be blown by the wind onto far-off concrete roads, with a tendency to drop in nearby soil which would lead to a higher survival rate.

Dutch urban ecologist Menno Schilthuizen also looked at the impact of large-scale urbanization on wildlife evolution. He calls cities “pressure cookers” on biological evolution. He argues evolution which used to take hundreds of years or more has been dramatically accelerated in cities.

In his book Darwin Comes to Town, Schilthuizen quoted some examples of species that have thrived and evolved in cities. For example, the mice living in different districts of New York City exhibit different DNA profiles. The urban heat-island effect causes the temperature in cities to measure higher than in surrounding areas. Snails living in urban areas become lighter in color to absorb less heat. Pigeons living in cities look darker because the melanin in their feathers insulates them from toxic metals. Scavenger crows in Sendai, Japan, learned to crack nuts with passing vehicles. Lizards in Puerto Rico have evolved claws more suitable for latching onto concrete. Moths in Europe have become less attracted to deadly artificial light. He cited these as evidence that urban environments are accelerating evolution of species in amazing ways.

Living with Animals

While wild animals seek to integrate into cities, humans are beginning to recognize the importance of environmental protection and inclusiveness of urban biodiversity. With the improvement of urban environments, more wild animals are returning to human life.

In the 1970s, water pollution in Singapore caused the otters in its rivers to disappear. In 1977, the Singaporean government launched the Clean River Campaign to improve water quality. In 1998, the aquatic mammal showed up again after a long absence. Today, about 90 otters share the urban space in Singapore. Despite a 2017 incident in which an otter bit someone, the locals have overwhelmingly enjoyed their company. In 2016, the mammal was voted the national mascot for the country’s National Day celebration. The Singaporean government has also placed icons and signs in the hot spots of otter activity to protect them and manage potential conflict with man.

“The formation of cities is the result of humans being attracted by the soil and water of certain locations, which is also attractive to wildlife,” commented Wang Fang. “Human beings didn’t congregate at these locations before wild animals.” Humans demand material and spiritual nourishment from urban biodiversity but doing so requires managing emerging problems effectively. “For example, the improvement of urban environments can cause the squirrel population to grow and start stealing our cat and dog food or chewing up our stuff. Similar afflictions have persisted in countries with great ecosystems,” Wang said.

In Berlin, Germany, the rivers, lakes, and green spaces in the urban area have attracted more than 3,000 wild boars. The animals’ settlement in the urban area has been troublesome for the surrounding parks and communities. In Bristol, England, more than 20 red foxes can be found per square kilometer in the urban area, which poses a threat to many rare terrestrial mammals and small birds.

China has faced similar problems in recent years. In Shenzhen, leopard cats were spotted in the residential area of Overseas Chinese Town. Wild boars found their ways to the city centers of Nanjing and Hangzhou, posing new challenges for urban governance. Experience has shown that measures such as poisoning or selective slaughter do not control the development of such species. Such intervention, on the contrary, can lead to ecological chain disasters.

Conservation of biodiversity in cities is more complex than in the wild. Wang Fang believes that in cities, man needs to be more proactive in biodiversity design and scientific management. In urban landscape design, biological management needs careful consideration. “For example, we need to consider how green space should be built, how canals should be built, and how the basic biodiversity of a city should be maintained through practical measures,” said Wang. “For some harmful species, you have to intervene. For example, everyone supports controlling rat infestations. In the farmland where pests and locusts are raging, control measures are a no-brainer.”

Much remains to be done on this front. The public is being discouraged from feeding wild animals. The government is expected to organize volunteers and researchers to monitor and research wildlife to gather more detailed information.

Environmentally Sustainable Cities

According to 2018 UN statistics, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and the proportion is expected to rise to 66 percent by 2050. Cities have become an important part of natural ecology. However, urban biodiversity is facing many challenges: climate and local environmental changes, invasive alien species, and urban expansion into natural spaces which is resulting in habitat destruction and fragmentation that could threaten the survival of man and other species. A path to healthy urban-wild development is a must.

In the ASEAN region, coastal cities are economically vibrant, but excessive resource development and growing pollution are threatening the development of biodiversity. The ASEAN Biodiversity Outlook noted that if urban development is left unchecked and environmental considerations are not prioritized against economic and industrial progress, cities might eventually become unlivable. The report described how over-exploitation of biological resources and invasive alien species as well as other forms of biodiversity neglect pose a major threat to the healthy development of ASEAN cities. ASEAN has called on all member states to take active measures to enhance the public awareness on biodiversity conservation and integrate biodiversity into urban development planning. ASEAN also proposed building Environmentally Sustainable Cities and established the Environmentally Sustainable City Award to highlight role models for sustainable development of cities.

In October 2010, the Singapore Index on Cities’ Biodiversity (Singapore Index) was formally adopted by the international community. The index includes three categories of indicators: native biodiversity, ecosystem services provided by biodiversity, and governance and management of biodiversity. The Singapore Index has been instrumental in helping local, national, and regional government departments share information on measuring biodiversity. The index enables city managers to evaluate and monitor the progress of their biodiversity conservation efforts against their own individual baselines and adjust strategies accordingly.

China and ASEAN have accelerated cooperation on building eco-cities. In 2015, China-ASEAN Partnership for Eco-friendly Urban Development was established to boost cooperation in green and sustainable urban development. Today, more than 20 cities from across the region are involved in cooperation in urban planning, water management, and other areas.

Cities are the common habitats of man and wildlife. Much remains to be learned about how they can coexist harmoniously in an eco-friendly urban environment.

Two otters in Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay, 2015. (DENG ZHIWEI)

A long-tailed macaque looks for food in Singapore’s MacRitchie Reservoir Park on July 7, 2015. (DENG ZHIWEI)

A team of resident volunteers conducts an animal survey in Shanghai. (WANG FANG)

Racoon dogs residing in the basement of a residential building in Qingpu District, Shanghai. (WANG FANG)

NO LONGER A CIRCUS ACT

Elephant-friendly tourism is providing better wildlife welfare

By Guo Meng

Elephants remain big business for many tourism venues offering interactions such as riding, dancing, painting, swimming, or photo ops. How do the elephants feel about these activities? Global consensus is that it’s mostly horrific abuse. The animals don’t know what it’s all about or why they get punished for failure. The gentle giants have tender hearts. They look muscular under the rough skin, but they are still sensitive to pain. Those used to entertain tourists with tricks at money-spinning shows are removed from their families and tamed by mahouts (elephant handlers) with abusive methods such as pointed hooks. After the shows, they are chained up and live miserably.

“For many tourists, traveling to Asia wouldn’t be complete without an encounter with an elephant, be it seeing a show, riding, or bathing one,” said Audrey Mealia, Global Head of Wildlife at World Animal Protection (WAP), an international animal welfare organization. “Yet sadly, elephant-loving tourists who want that ‘once in a lifetime’ opportunity are fueling demand for a mammoth sized problem that causes unthinkable cruelty behind the scenes, even if they don’t realize.”

The coronavirus has decimated the number of foreign tourists to Thailand, resulting in “layoffs” of more than 1,000 elephants used in the country’s tourism sector. Save the Elephant Foundation, a non-profit organization based in Chiang Mai Province of northern Thailand, has been seizing the pandemic as opportunity to save elephants. They became known for publicizing elephant abuse in tourist shows. Their mission is to save elephants from tourism and send them back to their native lands.

Elephant-Friendly Tourism

Despite the pandemic, Hug Chang Chiang Mai Elephant Camp in Thailand remains open to tourists. The camp is an eco-friendly tourism attraction that allows tourists to observe elephants. The manager on-site reported an average of 20 to 30 tourists to see the elephants every day before the coronavirus outbreak, but few to none since. The camp is a sanctuary for 12 elephants which receive good care from mahouts with regular checkups and walks in the woods. With proper treatment, elephants are very friendly with tourists.

Jirada Moran, a 5-year-old Thai TV star, visited the camp a few days ago. She prepared food for the elephants and watched them frolic in the woods and lakes.

“Elephants are our friends,” said Moran. “I’m happy to interact with them like this and express love for them.”

On June 30, 2020, the WAP released its first research report on excellent practices in wildlife-friendly tourism. The report showed that global wildlife tourism, which is growing at a rate of 10 percent every year, is expected to reach 12 million trips annually in coming years. The report also suggested wildlife-friendly tourist attractions include several core elements: no interference with the natural behavior of the animals, management and education of tourists, solid customer reviews, and earnest efforts to promote local wildlife protection.

With support and assistance from WAP, Chiang Mai ChangChill Elephant Camp has transformed from a tourist entertainment attraction to an elephant-friendly high-welfare venue. In Thai, ChangChill means “resting elephant,” which was chosen with hope that the elephants find a new life there. From observation platforms, tourists can acquire detailed information on the background of each elephant. Tour guides caution tourists to avoid flashlights, carrying food, staying alone, making loud noises, and getting too close to the elephants.

Over the past decade, the WAP has followed up on the welfare of captive elephants in tourism in Southeast Asia with three comprehensive empirical studies. The latest study evaluated the welfare condition of 3,837 elephants at 357 venues in Thailand, India, Laos, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia. The study found that 63 percent of captive elephants were suffering in severely inadequate conditions, 30 percent were in improved, yet still inadequate conditions, and only 7 percent were kept in high-welfare venues.

“Elephant-friendly tourism” is an initiative from the WAP to push tourism operators to stop selling and promoting travel products such as elephant riding and show, and to promote the transformation of the tourism industry to “animal-friendly” sustainable development. So far, more than 250 tourism operators from around the world have pledged to remove wildlife entertainment products such as elephant riding and performing.

Positive Changes

August 12 is World Elephant Day. Recently, the Thai Elephant Alliance Association organized a seminar for owners of private elephant camps in Chiang Mai to exchange views on the negative impact of the pandemic on camps and ways to help camp owners and elephant owners improve the welfare conditions of elephants.

“Ongoing suffering – but also some positive changes,” declared a WAP report titled Elephants. Not commodities–Taken for a ride 2, which evaluated the welfare conditions of 3,837 elephants at 357 venues in Asian countries from January 2019 to January 2020. The report concluded that 2,390 (63 percent) of the elephants were suffering in severely inadequate conditions at 208 (58 percent) venues, 1,168 (30 percent) were experiencing improved, yet still inadequate conditions, and only 279 (7 percent) were kept at high-welfare observation-only venues.

Distressing conditions at venues with severely inadequate welfare conditions include: frequent restrictions with short chains, demanding activity schedules, limited freedom for social interaction, and conditions that allowed for very little natural behavior. Venues with improved yet still inadequate conditions often offered half or full-day elephant swimming or bathing experiences. Despite tourist perceptions that elephant washing and bathing venues treat elephants well, concerns about these attractions are well documented because such close contact requires harsh training conditions. The attractions also prevent the elephants from ever returning to the wild.

The coronavirus outbreak has underscored the vulnerability of captive elephants and their dependence on tourism. Tourism venues have been struggling to feed the animals as of late. In Thailand alone, it is estimated to cost more than US$900,000 a month to feed all the elephants and a similar figure to pay mahouts. The WAP and other international and local non-governmental organizations have offered help to save the animals from hunger.

Zhao Zhonghua, chief representative of the WAP’s Beijing office, explained that wildlife-friendly tourism not only protects wildlife, but also better conforms to policy and market changes because operators’ risk drops drastically when they live more sustainably. It has emerged as an important way to protect natural heritage and biodiversity.

Elephants are marquee victims of wildlife mistreatment in the tourism sector. “Elephant-friendly tourism” is expected to soon become the new normal as the last generation of captive animals are returned to their native land.

The latest study evaluated the welfare condition of 3,837 elephants at 357 venues in Thailand, India, Laos, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia. The study found that 63 percent of captive elephants were suffering in severely inadequate conditions, 30 percent were in improved, yet still inadequate conditions, and only 7 percent were kept in high-welfare venues.

DEMYSTIFYING BIODIVERSITY

Interview with the Executive Director of the CAS Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute

By Wang Fengjuan

Booming economic development and a steeply increasing population have led the Southeast Asian subregion into multiple ecological environmental issues that demand analysis and resolution by China and ASEAN countries in tandem as regional players continue expanding international exchange and cooperation on biodiversity. China Report ASEAN interviewed Quan Ruichang, executive director of Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS-SEABRI) and a researcher at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden of the CAS, who elaborated on biodiversity cooperation between China and Southeast Asia.

China Report ASEAN: What is the current situation of biodiversity in Southeast Asia?

Quan Ruichang: Southeast Asia is one of the world’s three core tropical rainforest distribution areas and has some of the most abundant biodiversity and unique species in the world. It is also a key region for researching the origin, maintenance, and evolution of biodiversity. The adverse impacts of the booming population, rapid economic and social development, over-exploitation of natural resources, global climate change, exotic species invasion and hunting and illegal trade have caused the biodiversity resources in the region to fall under serious threat. A wide range of species have gone extinct rapidly, so protection of biodiversity has become an urgent and difficult task.

China Report ASEAN: CAS-SEABRI is a scientific and educational institution established overseas by CAS and committed to conducting cooperation on biodiversity research, conservation, and sustainability, but what are its main day-to-day functions?

Quan: The CAS-SEABRI mainly focuses on three aspects. First, we organize and implement major scientific research projects and interdisciplinary, trans-regional, and transnational investigations. So far, CAS-SEABRI has carried out nine large-scale joint expeditions in Myanmar, three joint scientific expeditions in northern Laos, and four joint field expeditions to study Cenozoic flora in Vietnam. A research platform for the “forest belt at 101 degrees east longitude” has been preliminarily completed. It consists of 10 large dynamic forest zones including four in China’s Yunnan Province, five in Thailand, and one in Malaysia which together form a forest belt spanning the core area of tropical Asia and stretching to the hinterlands of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau/Hengduan Mountains.

Second, we carry out strategic research and policy consulting on biodiversity conservation and sustainability. In response to declining forest resources in Myanmar, CAS-SEABRI provided technical consulting for the construction of the “China-Myanmar Eco-Friendly Demonstration Forest” in Myanmar, which involved planting 150,000 trees on 100 acres of wasteland. Since 2017, the research team of the CAS-SEABRI has cooperated with universities and research institutions in Myanmar to carry out Chinese hybrid rice experimental planting. The growth period of Chinese hybrid rice grown in Myanmar is 30 to 40 days shorter than in China. Compared with local rice varieties, the Chinese hybrid rice varieties grown at two experimental sites have shown better performance in terms of yield, disease resistance, and lodging resistance, with output up by 23.87 percent and 47.65 percent, respectively.

Third, we provide personnel training, technical training, and science popularization in fields of biodiversity and ecological protection. Since 2016, the CAS-SEABRI has organized training courses such as “Myanmar’s Tropical Plant Identification and Forest Management Training,” “Biodiversity Conservation and Community Development Workshop in Laos,” “Training Course on Breeding and Production Techniques of Major Crops in Southeast Asia,” “Advanced Field Course in Tropical Ecology,” and “China-Laos Trans-Boundary Wild Animals and Plants Joint Protection and Monitoring Technology Training.” The CAS-SEABRI has trained nearly 300 scientific and technological professionals for Southeast Asian countries.

China Report ASEAN: What difficulties and challenges have you encountered while researching biodiversity?

Quan: Intensification of human activities has caused the rate of species extinction to continue accelerating. Many species have gone extinct without ever being named, and many genes have been lost. Different ecosystems are facing fragmentation and sharp reduction in area because of human activities. We urgently need to strengthen the research, protection, maintenance, and rational utilization of biodiversity.

In terms of studying biodiversity in Southeast Asia, the biggest difficulties and challenges are as follows:

First, traditional slash-and-burn methods and large-scale planting of single cash crops such as rubber and oil palm have severely damaged forests in Southeast Asia.

Second, hydroelectric development in the Mekong River Basin poses a threat to the habitat of animals and plants, and mining has created a particularly serious threat for karst landforms.

Third, hunting and trading of wild animals is the greatest threat to the survival of many species. High-value species are still commodities actively sought by criminal groups, while species of lower value are traded for medicinal usage or food.

Fourth, supervision is weak. Due to relatively backward economic development, many governments have not paid much attention to biodiversity, and the corresponding regulatory and organizational structure is lacking.

Fifth, biodiversity transcends borders, and more attention needs to be placed on cross-border protection actions.

China Report ASEAN: Could you share one of your most memorable experiences studying biodiversity?

Quan: While doing research, we need to investigate, collect samples, and make specimens. The conditions for scientific expedition can be relatively difficult. Sometimes, we find bridges destroyed by floods and end up wading through water. In field investigations, it is normal to eat and sleep in the open air. If we are lucky, we can stay with a local family. We must beware of beasts, snakes, insects, and mosquitoes everywhere. You don’t want to get malaria.

One evening in June 2019, on our journey back from a scientific expedition in Htamanthi, Myanmar, a team member found a strange animal on the bank of a river several kilometers from our camp. It was lurking in the darkness, then turned sharply and ran away into the bushes. A colleague rushed to capture a snapshot with a macro lens normally used on plants. After returning to the camp, we guessed that the creature was a crocodile from the blurry photos. According to data, 23 species of crocodiles are on the books worldwide. It would be huge if we could discover a new species of crocodile.

So, we were determined to find it again and organized a “crocodile squad.” The next morning, the squad set off in two small wooden boats, switched their cameras to the telephoto and high-speed continuous shutters, but found nothing after a half day of searching. Everyone still had enthusiasm, so we decided we would look again whenever we had the chance. Searching, discovering, and researching are our daily routines. Difficult conditions do not stop our enthusiasm and love for scientific research.

China Report ASEAN: Since the establishment of the CAS-SEABRI, how many new species have been discovered in Southeast Asia?

Quan: We have completed nine comprehensive field expeditions in many places in Myanmar and discovered 63 new species of animals and plants. Among them, Magnolia kachinensis (Magnoliaceae) and Platea kachinensis are extremely difficult-to-find tree species in recent years. The scientific expedition team found white-bellied herons of which only about 500 are estimated to exist globally, as well as many rare and endangered species such as Bengal tigers, Panthera pardus, and clouded leopards. From 2018 to 2019, three joint field expeditions were carried out in northern Laos, and many animals and plants were photographed and recorded. So far, papers describing four new plant species and seven newly recorded species of plants have been published.

The research team of the CAS-SEABRI has compiled two special journals on new taxonomy of animals and plants and published related research in international science journals such as Zoological Research and Plant Diversity. Two special issues on new classifications of plants and related research were compiled on PhytoKeys, a peer-reviewed, open access, rapidly published journal. Through biodiversity surveys, we can correctly evaluate the status quo and trend of the fragmentation of the ecological environment in Southeast Asia, study patterns of biodiversity, formulate protection measures, and collect better data.

Quan Ruichang, executive director of CAS-SEABRI.

Team members of the China-Myanmar joint field expedition collect plant specimens in a wildlife sanctuary in Myanmar on May 28, 2019. (JIN LIWANG)

WILD DISCOVERIES

Tales of a China-Laos scientific expedition

Forest landscape on the banks of the Mekong River. (SIMON MATZINGER)

The remote areas of northern Laos have been mysterious to the modern world, and scientific expeditions in the wilds of this region are essentially journeys of explorations and discoveries. Laos spans a long horizontal swath of the Indochina Peninsula, which makes it a biodiversity hotspot and an ideal place for scientists to study tropical biodiversity and the evolution and geographical distribution of Southeast Asia’s forests.

China-Lao PDR Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation Collaboration involves scientists from the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute (SEABRI) of CAS working jointly on scientific expeditions, of which three have been carried out so far. The scientists dive headfirst into the wealth of life hidden deep in mysterious Laos.

Tropical Diversity in Laos

Laos is the only landlocked country on the Indochina Peninsula. Mountains and plateaus account for around 80 percent of the country’s land, and forest coverage is quite high. However, forest resources are declining rapidly because of extensive planting and forest exploitation, which is undermining the ecology and biodiversity of the country.

Over the last six decades, the XTBG has been engaging in the study of tropical rainforests and the relevant biodiversity along the China-Laos border. In the 1990s, it began conducting technological cooperation with Laos, during which the scientists organized training sessions in rural areas and provided guidance to locals on protecting cross-border biodiversity in northern Laos. In 2005, renowned ethnobotanist Pei Shengji studied the cross-border protective measures taken by China, Laos, and Vietnam, and proposed constructing a cross-border biodiversity reserve where the borders of the three countries converge. He named the reserve the Green Triangle. Then, researcher Chen Jin and his colleagues visited Vietnam and Laos to establish cooperation ties with relevant research institutes in the two counties, laying a foundation for biodiversity protection in the Green Triangle.

In April 2018, researcher Quan Ruichang and Dr. Song Liang from the SEABRI visited the nature reserves in Luang Namtha Province and Phongsaly Province in northern Laos for their first scientific expedition in the wild. They employed various investigative measures such as quadrat sampling, infrared monitoring, and visiting local farmers’ markets to study the birds, animals, fish, and plants as intimately as possible. They also discovered a couple of plant species newly documented in Laos, such as Aeschynanthus longicaulis, and Eleutharrhena macrocarpa, an endangered plant species in China.

In October 2018, Dr. Song took his team back to northern Laos. This time, the scientists gathered more quadrat samples and studied more species of birds, animals, and fish. All the collected information and research findings proved very helpful for learning about the biodiversity in northern Laos.

In April 2019, senior engineer Tan Yunhong led a China-Laos scientific expedition team to conduct field investigations in the Nam Ha National Protected Area in northern Laos. They camped in the field and framed a quadrat of one hectare. In the sample sector, the scientists completed relevant research and labeled all the plants. Alongside studying local animals, plants, and fish, they also investigated edible and medicinal plant resources in the protected area.

Along with the academic value, research of biodiversity is significant for sustainable development and protection of natural resources. Driven by the need for economic development and human subsistence, many species found only in small and limited areas could have already vanished without anyone noticing.

“I believe we can still find many valuable, rare, and unknown plant species in Lao forests, especially in isolated limestone forests,” said Ding Hongbo after participating in two scientific missions. Ding also expressed hope that the joint scientific expeditions would help Laos protect its biodiversity.

Scientists from the SEABRI have also launched scientific expeditions in the regions south of the Yangtze River in China, as well as Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, and islands of Indonesia. Scientists hope these efforts will help shine light on the evolution mechanisms and geographical distribution of tropical plant diversity in Southeast Asia.

Miraculous Plants

Many are fascinated with magical plants and herbs mentioned in folklore, myths, and legends. Ding Hongbo is among them. A member of the scientific expedition team studying the botanical diversity in northern Laos, Ding was tasked with categorizing and taking pictures of plants growing in the quadrat. The expedition was fraught with difficulty and even danger, but curiosity for the unknown drove Ding and his fellows to venture deeper and deeper into the wilds. The chance to discover a new species is an attractive reward for their unremitting efforts.

“Research and study of Laos’ plants started as early as 140 years ago, but the country still does not have a national Flora for all the plants found in its territory,” commented Dr. Tan Yunhong. “To study the phytochorion in a floristic region, you have to know the composition of plant species and their respective distribution characteristics.” The flora of a specific area, according to species and distribution, can be categorized and documented in a publication known as “Flora,” usually capitalized to distinguish between the two meanings. “Flora” is the basic material for floristic study and an indicator of a region’s academic standards.

Expedition team member Liu Qiang has an acute fascination with orchids and years of experience studying the flower family in tropical areas. When researching an evergreen broad-leaved forest in Oudomxay Province, Liu was able to quickly and accurately recognize and record orchid species he saw. The Lao researchers accompanying him were quite amazed especially considering that some of the orchids he identified had not even bloomed. Liu explained that many orchid species in the forest were not new to him because he found similar specimens in Xishuangbanna, a Chinese prefecture near the forest. During nearly a month of field investigation, Liu researched 118 species of 48 genera of the Orchidaceae, of which six genera and over 30 species had never before been documented in Laos.

But like many other plants in Lao forests, the prospects for the orchid family are bleak because of the country’s deteriorating ecology and diminishing natural resources. Locals have been replacing many indigenous trees with rubber trees, teak, or other more profitable trees, which has undermined the local environmental balance and destroyed the habitats of many plants. Numerous indigenous plant species are getting decimated by massive exploitation.

To survive, reproduce, and adapt to their surroundings, plants generate various chemicals through secondary metabolism. All these naturally existing molecules are essentially molecular biodiversity, and often become gifts for mankind. For example, a willow bark extract opened the door to aspirin, a groundbreaking drug. Quinine, which was first isolated from the bark of a cinchona tree, and artemisinin, a lactone derived from Artemisia annua, are tremendously helpful in controlling malaria. Paclitaxel, a compound used for cancer treatment, was first found in Taxus bark.

Laos has many ethnic groups which have developed a long tradition and abundant knowledge on using herbal medicines for basic health care. Promoting the planting and collecting of specimens with edible and medicinal value can help poverty alleviation efforts. The Lao living in remote areas can collect the herbs that sell for decent money.

During the expedition, the team researched a total of six plant species of the garcinia genus, two of which lack any distribution records in China. One species that measured one to three meters in height seemed incredibly short compared to similar species of trees that normally grow quite tall. Its leaves were also comparatively small. The fruit of the species turns red as it matures and is quite delicious. The team is still studying the ingredient composition of the garcinia genus, and the results are expected to help facilitate sustainable development of Laos’ medicinal plants.

Aromatic plants are also abundant in Laos. In addition to flavoring food, such plants are also used in pharmacology, religious rituals, and cosmetics manufacturing. Ancient records show that aromatic plants traded along the ancient Silk Road were considered luxuries. Pepper, cinnamon, cloves, and ginger were once as precious as gold. Because aromatic herbs were one of the most profitable commodities to transport, the Maritime Silk Road was also known as the “Road of Condiments.”

Somsanith Bouamanivong, deputy director of the Biotechnology and Ecology Institute under the Ministry of Science and Technology of Laos, noted that many Lao foods use local ingredients which give them unique flavors. Aromatic plants remain an important facet of Lao food culture. Such distinct flavors stimulate the appetite, and aromatic plants are not only profitable—their cultivation often enhances protection of endangered plants.

Lost Species

“Dawn on the Lao countryside feels like a fantasyland,” said team member Zhang Mingxia. “I would imagine myself waking up in a village surrounded by fog, able only to see the top half of a temple hidden in the water vapor and hear gibbons roar from a distance as tigers and elephants wander through the forest. This is the most gentle side of nature in my mind.”

But Zhang’s dreamy trance was eventually shattered in a village 30 miles from Luang Namtha where she came upon the skull of a Malabar pied hornbill, a bird in the hornbill family. The village head showed her the skull and explained that he acquired it while hunting on a mountain 10 miles from the village. The village head told her to watch out for tigers deep in the forest.

While on another field research excursion, Zhang invited a local guide to help her look for the bird in the place the village head had mentioned. They walked more than 10 miles around the village and camped on a mountain ridge. Day and night, they could hear gunshots, and they knew local people were hunting. Hunters often cook on the roadside, so Zhang saw many feathers of various kinds lining the roads. After two days of sleeping on the mountain, she finally came to terms with the frustrating reality. The species she could identify from discarded feathers far outnumbered what she saw and heard. She had to accept that the Malabar pied hornbill might have already gone extinct in this area.

That village is not the only place undergoing such changes. Li Guogang and Sun Nan are researchers who specialize in monitoring and tracking mammals. During the mission, they discovered animal corpses frozen in refrigerators and antlers of sambar and other kinds of deer mounted on the rooftops of local households. The researchers did not expect to find specimens of such precious animals so easily after setting up numerous infrared monitors in the forest of Xishuangbanna. The animals they saw post-mortem might never be captured alive by a camera for a whole year. All they could witness were rigid dead bodies waiting to be boiled and eaten.

A 2019 article in Global Ecology and Conservation announced that the tigers in the Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area in northern Laos had died out. The region was the only place in Laos confirmed to have tigers, so the article declared tigers extinct in the country. The author also suggested that leopards may face the same fate. Every time a species is wiped out on this planet, it becomes even more crucial to protect the surviving ones. The task becomes more pressing with each passing day.

Big birds and animals are the preferred targets of hunters. If local people inhabiting the areas around forests cannot escape poverty or benefit from protecting the environment, mapping out protected areas is useless. In the Shangyong Nature Reserve, a district adjacent to Laos’ Nam Ha Protected Area and a subsidiary of the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in China, an Indochinese tiger was photographed in 2007. It was the last time an image of the species was captured in China. Over the past three decades, species such as gibbons and large hornbills have disappeared alongside tigers.

(We thank the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden and the Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for their contribution to this article.)

Abroma augustum blossoms. (ZHU RENBIN)

Vanda brunnea, an orchid species found in Laos. (LIU QIANG)

Red plumbago indica flowers. (ZHOU ZHUO)

A camp site in Nam Ha National Protected Area. (LI GUOGANG)

The scientific expedition team identifies plant specimens. (SONG LIANG)

A Lao villager displays the trophy wings of a crested serpent eagle that was hunted. (ZHANG MINGXIA)

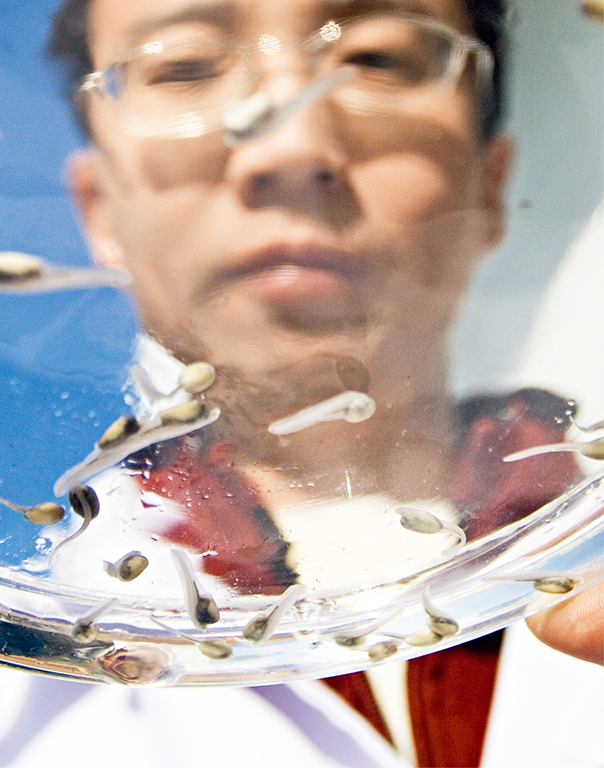

Members of the scientific expedition team observe fish specimens. (GAN ZHONGLI)

BIODIVERSITY IN THE KARST REGION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND ITS CONSERVATION

The forgotten limestone ecosystems of Southeast Asia

By Alice C. Hughes

A view of Mandalay, Myanmar. (SANTI SUKARNJANAPRAI)

When we think about biodiversity in Southeast Asia, we generally think about the verdant forests. However, one special part of the Southeast Asian landscape is frequently forgotten: the limestone hills that make up around 800,000 square kilometers of Southeast Asia and host a suite of rare and endemic species unable to survive anywhere else.

Most of the species that inhabit these limestone hills are so specialist that they may only occur on a single limestone outcrop, just one hill. These species include unique orchids, begonias, gesneriads, snails so small they could fit in the eye of a needle, and geckos so beautiful that entire populations of a species are often collected to extinction for the pet trade when the species is first described by scientists. Given the burgeoning demand for cement across Southeast Asia, many species are at risk of going extinct before they are even scientifically described.

The majority of the species that depend on these limestone hills are still unknown. In fact, 90 percent of cave invertebrates in China estimated as undescribed, and probably similar percentage of other cave and karst dependent species, remain undiscovered across the region. A single karst hill can host 12 or more site-endemic species, found only on that one site, so losing a single karst can mean the extinction of the species dependent upon that system.

This wide array of fascinating and fragile organisms together form ecosystems like no other, including even each other. The species which live in karsts are unique, and their isolation makes them like remote islands in many ways, meaning their species are frequently unique; but the diversity is higher than the equivalent island systems—as they can host both specialist and non-specialist species.

Karst Specialists: What Makes Them Special

One of our major activities is surveying bats across the region. Bats are an incredible group of species, making up the second largest group of mammals at over 1,400 species, but only around 50 percent of species present have even been described in Southeast Asia. Our research on bats actually spans over 12 years, and the whole of the Southeast Asian region, though our main focus now is in line with our other karst projects and we have already measured thousands of bats as part of the study.

Our research includes many aspects of bat behavior from diet selection, migratory patterns to population genetics. Just within our institute (Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden), we have listed 42 species to date. These species include new records for China such as the first record of Kerivoula kachinensis, and interesting observations in rare species like the Harlequin bat and possible migratory behavior in a whole suite of species. Some of these bats may be migrating thousands of kilometers, but we are still collecting the data to see what is moving where so we can better understand their movements using isotopes in their fur to see where they may have travelled across the year.

Bats are often featured as movie monsters, yet many species are important as pollinators, seed dispersers and for pest control, and they have a huge suite of fascinating adaptations for their habitats. This means that though some species may migrate thousands of kilometers, others may be restricted to a single karst, unable to fly outside the forest due to adaptations which make flight expensive and calls only useful over short distances. Every part of a bat is adapted to its habitat and diet, with species like Thailand’s “bumblebee bat” (Craseonycteris thonglongyai, the world’s smallest mammal) which only uses caves with a very particular type of limestone, probably because of the way this limestone erodes; as this determines the presence of structures that different species of bats roost in.

Another group we have been focusing on are the karst geckos, including the true cave geckos (Cyrtodactylus and Goniurosaurus) and other species which can also show endemism on karsts like Hemiphyllodactylus. Karst geckos are a very charismatic group of animals which show high site-specific endemism to karst hills, meaning that each expedition reveals new species; we are currently working to describe potentially eight or more new species from our last expedition. Like for many cave endemic species, we are only starting to understand the patterns of diversity and endemism in this group, and we hope our study will shed new light on the processes of karst colonization and enable their conservation into the future.

The diversity of life forms inhabiting karsts demonstrates how valuable these habitats are. Cave fish, for instance, are often highly-modified relatives of river fish. In colonizing karst landscapes, they often lose the ability to see (frequently losing their eyes altogether) and lose all pigment, becoming a ghostly pink-white color. These species can be found in the depths of caves far from the outside world, largely living off the detritus brought in by the bats, and the other species which depend upon it. Like other cave-dependent species, cave fish show very high levels of endemism. We still know very little about their distribution over the region, so our studies will provide new insights into how different types of organisms may colonize karsts in different ways.

Surveying the immense diversity of karst invertebrates requires collaboration, and we are presently working with global experts on the elongated Trechine cave beetles, as well as centipedes and millipedes, while outside the caves we focus on karst microsnails, which can have as many as 100 species from a single site! The vast majority of these cave-dependent species have never been scientifically described, meaning potentially hundreds of new species which would remain unknown and unprotected without our efforts.

Amazingly, despite their love of sunlight, some plants like Urticaceae and Begonia are frequently found in even the lowest of light levels in caves. Though the mechanisms that urticaceae are still unknown, begonia uses a system a little like the light reflectors often used on roads to reflect light back into their cells to use again for photosynthesis. This strategy makes the leaves glitter blue-green in torch light. These and other plant species also depend on karsts for survival, showing just as high levels of diversity and endemism as other cave-dependent groups do. Like other cave and karst dependent species, these species are often isolated to only a small area, and like karst geckos, they are vulnerable both to the loss of habitat and targeted collection.

After years of work, we are beginning to understand these complex, hidden ecosystems, but the high diversity and the great threats they face make further research all the more important. With so many undescribed species, this is a daunting, but worthwhile, task. If we do not act to preserve these systems then we will lose a vast wealth of unique species without even knowing it.

Myanmar and Its Karsts

Myanmar is an incredibly diverse country, yet we are still only scratching the surface for much of its biodiversity. The challenging political situation means the country was largely closed to biologists for many years, yet with potential development to come we now face the urgent task of prioritizing areas for protection before they face development.

Many of the sites we inventoried had never been previously surveyed, and further work will be needed to completely inventory the species in each of them. Our work included sites across Myanmar, with one site only accessible using a huge rock transportation lorry followed by a steep hike. That particular cave was so full of bats that every surface was caked in Guano, and unlike most caves, this one had so many bats that the walls actually crawled with ticks, yet we recorded new locations for a number of species. On emerging from this cave, we were greeted by several soldiers and police, who were there probably more due to curiosity than security. They seemed surprised to see our all-female team of four nationalities emerging from the ground and probably appearing like we had spent several years under it.

Sadly, from a biological perspective, not all the caves we visited were so little accessed, and many sites had already been converted into temples or tourist caves. Though some of these only opened some areas of the cave, others projected light onto almost every inch of wall and floor and more closely resembled casinos than the caves we (or bats) preferred to visit. In these caves, the number of remaining species was hugely variable, but many contained only the most tolerant and generalist of species, and some had no bats at all. Yet, when done well (i.e. leaving some areas undisturbed and only lighting areas when people walk by), tourism can provide useful revenue for preserving cave sites and their biodiversity.

The caves and karsts of Myanmar took us across the country, providing many insights into a region with an incredible history for its people as well as its other species. Standing near the top of a steep hill in the mouth of a narrow cave, we watched a train steam through the valley below, which reminded me of the challenging circumstances under which many of the region’s railways were laid and the lives lost to build them. Yet some of our sites made us reflect on an earlier time in human history, such as the Padal in caves. These caves lie nestled at the end of an island in a reservoir, surrounded by the towering Nwalabo karst mountains, which remain largely unexplored and include cave paintings of over 15,000 years old, though deposits indicate that these, like so many caves, have been an important part of human history for over 65,000 years.

In Myanmar, like the rest of the region, we still have so much to learn, as many of the sites we visited hosted their own unique species and many additional sites remain entirely unchecked. Our work is allowing us to begin to understand patterns of diversity for at least some species.

The karsts we survey also vary hugely in their shape and size, from the extensive and rugged karst landscapes of Ha Giang and Lao Cai in Vietnam (unrecognized centers of diversity and endemism for the whole of Southeast Asia), and the famous karst islands of Cat Ba and Halong bay (which despite their fame are still understudied, and have many new species to describe), to isolated karsts across the region. None have complete inventories, and outside Vietnam few have any form of protection, and almost all need better protection and more research.

About the author Alice C. Hughes is a research fellow at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden of Chinese Academy of Sciences and a council member of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation from 2017-2019.

90%

In fact, 90 percent of cave invertebrates in China estimated as undescribed, and probably similar percentage of other cave and karst dependent species, remain undiscovered across the region.

The bumblebee bat, the world’s smallest mammal. (YUSHI OSAWA)

1,400 mammals 50%

Bats are an incredible group of species, the second largest group of more than 1,400 mammals, but only about 50% of them have been described in Southeast Asia.

Color pattern variation in Cyrtodactylus chrysopylos from the Padalin Cave, Shan State, Myanmar. (PLAZI.ORG) A. Adult male B. Adult female C. Adult female D. Adult male

The Padalin Cave in Shan State, Myanmar. (PLAZI.ORG)

BACK FROM THE BRINK

Once thought extinct, the population of the crested ibis is growing after four decades of conservation efforts in China

By Zuo Lin

A foraging crested ibis. (VCG)

About 200 kilometers south of Xi’an, capital of southwest China’s Shaanxi Province, along the Hanjiang River in the Hanzhong Basin, is Yangxian County. Abundant rainfall brings lush vegetation by early summer, making the area attractive to the crested ibis (Nipponia nippon), a medium-sized, white-plumaged wading bird with bright red on its face, legs, and tip of bill. A slight tinge of orange can be spotted on their outstretched wings. Residents of the area have become familiar with the birds, and flocks of the ibis can frequently be found probing around for small fish and shrimp in rice paddies.

In years past, the crested ibis was common throughout Northeast Asia from Russia to China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula. Because of habitat loss, its population declined rapidly in the 1970s. The species was thought extinct in the wild until an exciting discovery in May 1981. The last seven wild crested ibises in the world were found in Yangxian.